by Abhinav Sukla, Co-editor Sidereal Times

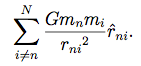

Physicists and astronomers have proposed countless theories about the cosmos. Until recently, however, there was little means through which to test their theories; often, observational data was not detailed or plentiful enough to verify them. Thus, scientists came up with a method known as N-body simulations when computers began to evolve, a simulation that allowed them to track the motion of multiple astronomical bodies. In principle, N-body simulations are simple; the only significant force acting on these astronomical bodies is the gravitational force, which can be determined by Newton’s equation of gravitation. In order to calculate the total gravitational force on an astronomical body, it follows that one must simply integrate all of the gravitational forces acting on each star, producing an equation like so:

Essentially, the gravitational effects of all the other stars on each individual star is calculated, and using this, a new velocity and position is found for each of the stars at the next timestamp. Although this method was the most accurate, most computers lacked the computational power to complete this process for a large number of stars, since the number of calculations needed for N stars was N^2, meaning a simulation with 10^4 stars would need 10^8 calculations for each iteration. Despite the computational inconvenience, this method remained prominent for many years. That changed with the development of the revolutionary Barnes-Hut simulation, a clever approximation that drastically reduced the required computation and made N-body simulations accessible to a larger number of astronomers

The Barnes-Hut N-body simulation uses an approximation method to make running N-body simulations far easier. Essentially, the algorithm divides the 3D space into smaller and smaller cubes until there are only 1 or 0 stars in each cube. Then, it treats far away stars as a single, massive star, and calculates their effect on a given star using the center of mass of the cube those far away stars are in. It is a bit like looking at a far away city skyline; you don’t need to see every individual window to determine the approximate brightness. For closer stars, it uses the smaller, subdivided cubes in order to make calculations. This ensures that the stars that have a greater effect are considered while far away stars are approximated. The original algorithm scaled as N^2 for N stars, but the Barnes-Hut version scales as NlogN, significantly reducing the number of calculations. Drawing on the prior example, a simulation with 10^4 stars would only require around 40 thousand calculations using the Barnes-Hut algorithm, a significant improvement from the 100 million needed using the original brute force method.

With the improved performance enabled by the Barnes-Hut algorithm, N-body simulations became far more accessible. However, the amount of computation involved was still significant for most computers, so many projects “borrowed” computational power from many different computers in order to run their simulations. With the advance of GPUs, however, computers can run multitudes of calculations all at once using matrix multiplication. Today, astronomers throughout the world utilize N-body simulations to chart the position of galaxies over time, model cosmic structures, and even predict the final fate of our universe. As computational power and modeling mechanisms evolve, our ability to understand the night sky above us will only grow.