by Rees W. Morrison

What celestial object is so densely compact that a teaspoonful of it would weigh as much as Mount Everest (800 trillion kilograms last time it stepped on the scales)? What object has a gravitational force that is 100 billion times stronger than Earth’s (you’d have to zip along at one-third the speed of light to escape the star)? And what if you knew that the diminutive object has a diameter of the 11 miles from Peyton Hall to the center of Trenton, yet even so it whirls its mass of one and a half Suns (yes, you read that correctly) more than 100 times every second? Such a hard-to-believe object would be one of nearly 4,000 known neutron stars.

Did I say that neutron stars are awesome and fascinating?

They are the left behind remnant of a star of between eight and 20 or so solar masses that runs out of fissionable fuel and suffers the almost instantaneous collapse of its iron core. That implosion triggers a colossal supernova, with the 20-kilometer remnant that consists mostly of neutrons blazing away at over a 100 billion degrees Kelvin (compared to the Sun’s comparatively frigid surface of 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit, and its tepid core of only 27 million degrees Fahrenheit). Topping it all off, its magnetic field (“magnetosphere” to fans) exerts the force of 1 trillion gauss – that’s 300 million times stronger than a sunspot, enough to pull atoms apart if something were to approach the neutron star.

Now, that’s a lot of metrics. How in the world (or out of this world) do astrophysicists calculate those mind-boggling figures? The answer to that question, or at least an excellent start, can be found in a recently published review on arXiv: Stefano Ascenzi, Vanessa Gaber and Nanda Rea, Neutron-star Measurements in the Multi-messenger Era, (Jan. 2024) https://arxiv.org/pdf/2401.14930

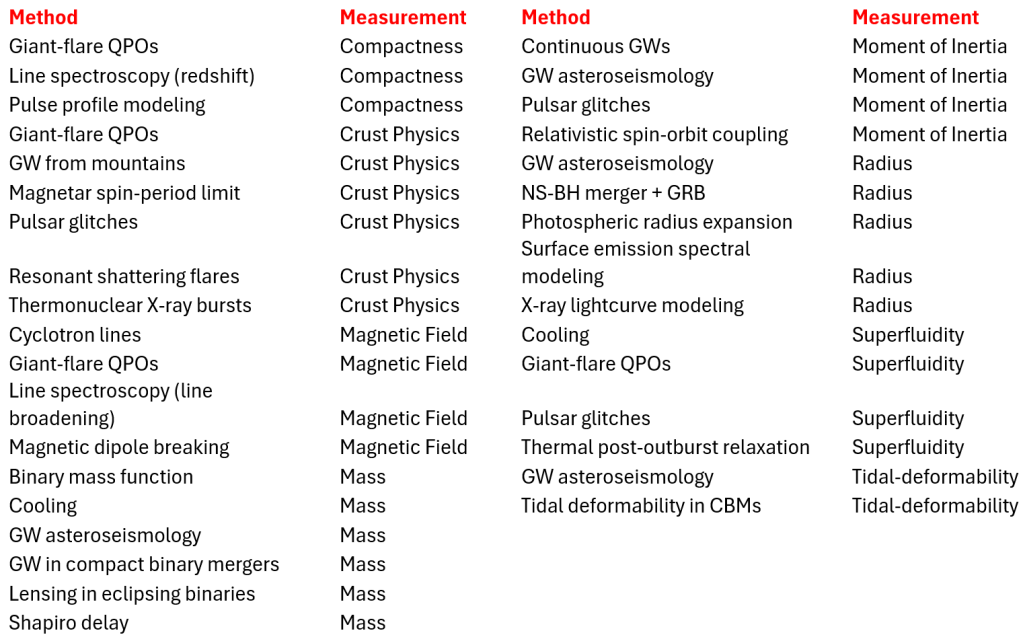

Based at space research institutes in Spain or Italy, the authors start with a lucid overview of what is known today about neutron stars from electromagnetic radiation, neutrinos and gravitational waves. Following that introduction, they carefully and clearly explain “a schematic overview of the different techniques used to study these extreme objects and how reliable these approaches are.” Over the next 28 pages they tackle the methodologies behind inferring eight important neutron-star measurements. In addition to the mass, radius, compactness, and magnetic field of neutron stars (in general, as there are eight-to-ten varieties of such stars), they also cover moment of inertia (a measure of how resistant the neutron star is to changes in its rotational motion, involving its mass, how far the surface of the star is from its center, and how the mass is distributed), tidal deformity (when a neutron star orbits another star or black hole and gravity distorts the neutron star), the crust (which is on the order of 10 billion times stronger than steel and sometimes ruptures as an unimaginable starquake), and superfluidity (inside the star the material flows with zero viscosity, meaning without losing kinetic energy).

The authors explain the strengths and weakness of several methods to calculate or infer each of the measurements. And their synoptic review adds more: they explain which energy levels – gamma rays, X-rays, radio waves, etc. contribute to the data and calculations. Finally, they present their views on how much the method depends on the so-called “equation of state” selected by the researcher. Equations of state integrate the density, pressure and temperature of a neutron star, and there are scores of them that make different assumptions or cut-off points.

The table below states the measurement in the “Measurement” columns and in the “Method” columns several methodologies based on observables (like we can observe the spectrum and the spin rate of neutron star that beams at us – a pulsar) and how those observables produce inferred values. In alphabetical order, the acronyms are BH = black hole; CBM = compact binary merger; GRB = gamma-ray burst ; GW = gravitational waves; NS = neutron star; and QPO = quasi-periodic oscillation.

The authors acknowledge that “fully covering the extensive literature on this topic is beyond the scope of this review”, but they cited an impressive 633 references! Among them are more than 30 reviews, which are the best way to survey and plunge into a specific topic.

At the end of their opus, the authors summarize what they have done – and reiterate the theme of this article:

The study of [neutron stars] presents fascinating opportunities for scientific exploration. These compact objects, characterized by strong gravity, high densities, large magnetic fields and fast rotation, offer insights into the properties of matter and strong interactions under extreme conditions that we cannot replicate in terrestrial environments. However, as I demonstrated in this review, measuring the characteristics of [neutron stars] and using these to constrain dense-matter physics is a challenging task.

PS: Rees would be very pleased to talk about neutron stars and related topics with any interested reader. He can be reached at rees@reesmorrison.com